|

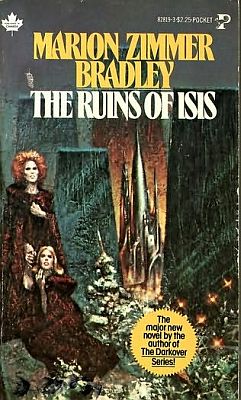

| Cover by Kelly Freas |

| THE RUINS OF ISIS Marion Zimmer Bradley New York: Pocket Books, August 1978 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-671-82819-? | ||||

| ISBN-10 0-671-82819-3 | 298pp. | SC | $1.95 | |

In the course of studying the matriarchal culture of the planet called Isis, anthropologist Cendri Owain Malocq had to cope with contending political factions, earthquakes and tidal waves, and an incipient rebellion. She also had to face problems she had brought along. One was her husband Dal. Normally loving enough, he was driven by the conditions of Isis to his own sort of rebellion. Then there was the fact that she had misrepresented herself to the Mother authorities on the planet.

Children were everywhere in the city, and Cendri continually puzzled over how they came to be. She observed that men were kept apart from women — except for Companions, which only Ladies of high station possessed. They had to be getting together somehow; she just didn't know how.

In her conversations with female friends she made, like Vaniya's third daughter Miranda, there was frequent mention of the thrice-yearly ritual the women of Isis referred to as "visiting the sea" — a phrase which occcasioned furtive smiles and giggles. It seems to me that, being trained as an anthropologist, and having knowledge of many worlds as well as experience on cosmopolitan University, Cendri ought to have been able to at least hazard a guess that the phrase was a euphemism for some sort of periodic mating ritual. Here I get a little of the same feeling I got from the ominous premonitions in Web of Light: Bradley is dropping broad hints that this is a mating ritual, and the reason she has Cendri missing those hints is obscure. Consider this conversation:

"It would seem strange to me to consult the wishes of a man, especially of a Companion," Miranda said, and she was frowning a little. "I had thought perhaps it is the reverse of the way it is here; that perhaps in your worlds a man owned a woman and and was responsible for everything she did . . ." Cendri shook her head. "No, although I believe there have been worlds—Pioneer, many generations ago—where this was true. And in some cultures a man is required to provide for the support and nurture of any children he has fathered." Miranda said, "That does seem strange, for a man to be responsible for a child; how can any man possibly know that a child is of his fathering, unless he has kept the woman locked away from everyone else?" Again she seemed on the verge of saying something else, and again hesitated, drawing back; Cendri wondered if indeed the time were ripe to ask something about the unknown mating customs of Isis, but instead Miranda frowned a little and said, "It seems so natural that the woman, who bears the child, should take all responsibility. Yet I can see that your way could have its—its attractions," she added, her lips curving for a moment in a faraway smile. Cendri wondered who had fathered Miranda's child; if, for a moment, she had actually forced Miranda to think for a moment beyond her own cultural prejudices. Then Miranda said, "But if you had—had a child, and separated from your life-partner, as I from mine, would you not simply do as I have done, return to your mother and sisters so that they could care for you and your baby?" Cendri laughed. "That is the very last thing it would occur to me to do. I am not even certain where my own mother lives now; she could not wait for me to be old enough to go to my chosen lifework as a Scholar, so that she could return to her own! I have not seen her since my seventeenth year! I suppose someday we will meet again, as friends, but each of us has her life to live; on our world we do not recognize biological ties after a child is old enough to fend for herself. "That seems to me as cold-blooded as the fish," Miranda said with distaste. "How else are women distinguished from animals, except by the nurture they give their young?" She laughed, then said, "It is good to hear someone challenge the ideas I take for granted! I like talking of such things with you, Cendri. I think I shall always like to do so, but I should warn you not to speak too freely of such matters to the women of this household. Many of the women here would be shocked and disgusted by the way we have been talking, they would think you dirty and perverted for talking of such things—and me no less perverted for being willing to hea them spoken! Don't tell them, will you, Cendri?" She smiled at the off-worlder and sniffed deeply. "I thought so; the fish-flavoring herbs are in flower, by the South wall. Come, let us gather some and take them to the women in the kitchen; they will want to gather them while their fragrance is strongest, and dry them to season the fish when next we visit the sea." She gathered a bouquet of the strong-scented greyish pink flowers to take to the kitchens, Cendri helping her. When they came to the kitchens, one of the women wrinkled her nose in disgust. Pheu, you smell like a fish dinner, Miranda, you smell as if you have been visiting the sea—" Miranda laughed. "well, and so I have; you can tell that by looking at me," she said gaily. The other woman turned away, abashed. "What a way to talk, Miranda! And before the distinguished guest!" "You first spoke of it," Miranda said, laughing. "We are all grown women here! And if we want herbs to season our fish, we must then smell like the sea! And I like the smell, for it tells me the season for visiting the sea is near—what is it, Zamila? Does the smell make it too hard for you to wait?" She crushed the strong-smelling flowers between her palms, bruising them, and as the aromatic smell spread through the room, the women began a little nervous giggling which Cendri did not understand. Dal, too, when Cendri got back to the upper apartment which they shared, wrinkled his nose against the strong smell which clung to her hands. "What in a hundred worlds is that stink, Cendri?" "An herb of some sort, used for seasoning fish; I was helping Miranda to gather it," Cendri said, abstractedly. Did the talk of "visiting the sea" have somenting to do with their seasonal religious festivals, then? – Pages 78-81 |

The one aspect of the story which I thought would not raise new complications was Cendri's participation in this ritual. The event had been mentioned before, and there had been references to fish. Surely she would understand its purpose and find an excuse to merely observe without participating.

But this is not the case; Cendri continues to miss those hints. And so, invited by Laurina, she finds herself at the seashore, having watched the men spear-fishing, having eaten the cooked fish, waiting near midnight with the women of Isis for she knows not what.

"Then she saw them coming, a long solemn line, up from the shore. Cendri heard some woman—a very young one, by the sound—giggling nervously, and someone near her reproved her in a whisper. At her side Cendri felt Laurina's fingers clutch at her arm, with a deep, convulsive gasp. And suddenly Cendri understood." "So this is how men and women come together. Solemnly, by moonlight, in ritual: "visiting the sea." She should have known. Miranda's jokes about fish dinners. And now she was here, a part of it. Something in Cendri panicked, cried out to her wildly to get away, she had no part in this, she could not . . . yet some other part of her was excited and exhilarated, wanting to see it through, knowing that anyway there was no way she could remove herself now from the women of Isis, clustered here and awaiting their seasonal ritual of mating." – Pages 229-230 |

Cendri entertains eleven men1 (or is it thirteen?) who greet her with the ritual phrase, "In the name of the Goddess who has bidden us to visit the sea..." Each one, she finds, is gentle and respectful. Most hold her afterward and whisper a brief endearment before leaving her with the traditional sea-gift. One, a youth, even weeps at the intensity of the experience.2 She, however, feels little emotion — until, after the last man departs with the dawn, Laurina embraces her...

So this is a Marion Zimmer Bradley sex scene. To my male sensibility it's arguably prurient, especially in the lesbianism aspect. Yet it also fits into the logic of the story. Even Cendri's unlikely cluelessness is required to set up the scene. For with it, Bradley has a few points to make. Point 1: The sexual drive in most adult men and women is strong, and prohibiting its expression often brings undesirable results. Therefore, it is seldom absolutely prohibited. Point 2: Sexual feeling is strongly tied to emotional bonding. In a society which denies the opportunity for women to bond with men in friendship, but encourages them to become friends with each other, any emotion attendant to sexual encounters will naturally follow the friendship bond. Point 3: While anthropology teaches that neither male or female homosexuality should be regarded as unnatural, and therefore condemned, its occurrence will be minimized only where men and women have equal status, and sexual intercourse does not become a universal competition to see who can rack up the highest score or a badge of legitimacy immediately upon entering puberty.

Biology tells us that males of mammalian species will go to great lengths to make sure any offspring is due to their sperm, not some other male's. But they act either before conception, by dominance keeping other males from touching their females, or after birth, by killing the female's young and re-impregnating her. Human males don't use such extreme measures to protect their lineage, of course, but in the past the chastity belt and the purdah served as well, while today social strictures and contraceptives do the job. The way Bradley sets up the situation on Isis, however, neither option is open to them. So this is true to anthropological reality; for whether human or lower animal, males will avail themselves of any chance to mate. It follows, then: On Isis, no one knows who the father of any child is, or cares. She makes a point of having female characters say so explicitly several times.

Marion Zimmer Bradley was known as a feminist writer. That may well be true of her work as a whole; but based on this novel alone I would call her writing feminine rather than feminist. She devotes a great deal of attention to the emotions of her women characters — especially to Deoris, with her moody petulance, her dependence on her older sister. As for Domaris, there are frequent descriptions of how much she adores Micon and enjoys bearing his son. However, Bradley does not mention the actual union of Domaris and Micon to conceive a son; the two-page chapter titled "The Union" is instead about the induction of Domaris into the sacred Order of Light. Two chapters later, "The Secret Crown" shows us Domaris and three other women outdoors gathering flowers for a festival, with a casual breastfeeding scene of one's infant daughter. The crown referred to is not some buried relic invested with magical powers, but Domaris's discovery that she does indeed bear the child, thus finally wears the crown of true womanhood. This being the case, the lack of mention of her joining with Domaris is puzzling. I'm not calling for a sex scene here, but surely Domaris's attitudes would argue against Bradley leaving this transcendent event entirely undescribed.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.