|

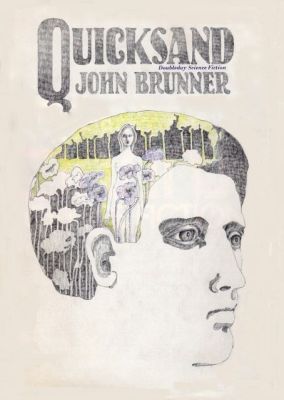

| Cover by Emanuel Schongut |

| QUICKSAND John Brunner Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1967 |

Rating: 5.0 High |

|||

| ISBN-13 978-0-879-97245-5 | ||||

| ISBN-10 0-879-97245-9 | 242pp. | HC | $? | |

Dr. Paul Fidler1 was psychiatric registrar at Chent, a mental hospital in the English Midlands. He had a nice but modest house in the relatively luxurious neighboring town of Yemble. He had a beautiful wife, Iris, from an uppercrust family (her father's money had paid for the house.) He was competent at his job and well liked by his colleagues.

And yet Paul Fidler's mind was filled with feelings of unsuitability. The hospital, in an old estate, seemed cramped and run-down. He got on poorly with his boss, who struck him as bureaucratic and overbearing. His wife didn't suit him; he wanted children and she didn't — didn't even want to adopt, as it would crimp her style. He felt he didn't suit his job, and was constantly second-guessing himself; his imagination conjured up visions of other versions of himself taking alternate pathways in life, most of which led to disaster. (The stream-of-consciousness narrative, in Brunner's novel, takes the form of statements beginning with a hyphen.)

And, this particular February day, he found even the countryside unsuitable.

Most of the day a lid of grey cloud like dirty cotton-wool dressings had lain over the district, shedding halfhearted rain at intervals. Now, with not long to go before sunset, a cold wind was brooming the clouds eastward and wan sunlight was leaking through. * * * When he first came here, he'd liked this country: irregular, dramatic, as if the red rock underneath the red soil were heaving itself up preparatory to the titanic effort of building the mountains of Wales. A landscape appropriate to castles, fit setting for heroic deeds and grand gestures. –I suppose it takes a Paul Fidler to make it a backdrop for failure. – Page 11 |

Then the girl appeared.

Fidler's first notice of it came when he was at his favorite pub, having downed a pint followed by two shots of scotch. A traveling salesman named Faberdown staggered in clutching his arm, scratch marks and a bruise livid on his face. His story was that when he stopped his car to relieve himself, a naked woman attacked him out of the woods. Fidler of course examined the man, finding his arm to be broken and calling for the ambulance from Chent. He also found reason to suspect that Faberdown might not be telling the whole story.

Directly a police search began (Inspector Hofford first preventing a Mrs. Weddenhall2 from going in with her wolfhounds and a shotgun posse.) Fidler came along since indications were that a deranged person was at large. Shortly he discovered the girl hiding in the woods. More accurately, she announced herself by calling, "Tiriak-no? She stood quietly in the flashlight beam as Dr. Fidler tried to make sense of her utterance. He saw a young woman around 5 feet 5 in height, well proportioned — and she was indeed naked. He gave her his coat and she came along quietly to where the Inspector and others were gathered by the road. She said nothing further, but approached the cars with fascination; it was as if she had never seen one before. Naturally she was committed to Chent for further investigation.

–She can't be under any illusions about where she wound up. Things may baffle her but people she does appear to understand. Packed in head to foot in what were once fine stately rooms but now stark with chipped plaster, faded ugly paint, bars at the windows and locks on the doors. The keys in his pocket jingled, not audibly but in memory. –And I told Natalie this afternoon we had eighteen free bedspaces. Whose word am I taking for that? Every ward so crammed we only have room for a poky little locker too small to hold a kid's toys alongside each bed. Anything too much or too numerous for the locker to hold: taken and shut away. How do people reassure themselves of identity? Belongings, possessions, mementoes: The solid proof that memory does not lie. And bit by bit we chip away the mortar of their lives. Christ, how did I ever wander into psychiatry for a living? – Page 45 |

She was apprehensive and withdrawn, really trusting no one but Dr. Fidler, but she cooperated willingly enough. Gradually she began to learn English, pointing to objects and memorizing their names instantly. Many things seemed unfamiliar to her; oddly, television did not. Her name, she said, was Arzheen. There was no sign of insanity, but she refused to explain who she was and where she came from. She was a great mystery, and Fidler became determined to get to the bottom of it. There was the chance of a career-making paper in some journal, as his colleague Dr. Adler kept reminding him. But Paul had a more personal motive: he was sure she was sane, and wanted to prevent her whiling away her life in the dreary confines of Chent.

It was thought she might be a foreigner with a head injury, so arrangements were made to take her to Blickham, a town with a portrait studio and a larger hospital that had an x-ray facility. That facility was tied up with other cases, so Paul took her for pictures. The camera apparatus made her uncomfortable, but Paul was able to persuade her to sit for an exposure. When she caught a glimpse of the x-ray machine, however, she went wild with fright, injuring a nurse and shouldering Paul out of the way to escape. (She did not just shove him aside with her shoulder; she unerringly drove the point of her shoulder into his solar plexus so that he doubled up, his breath gone, as she darted past. This, and the way she injured the nurse, confirmed what her treatment of Faberham had suggested: she had a remarkable ability at unarmed combat.)

Fortunately for Fidler's career, she stopped running outside the hospital and once again cooperated as he took her back to Chent. Ultimately, quite by chance, he put her into a hypnotic trance and was able to get answers regarding her origin. The story she told was fantastic. She said she came from a place called Llanraw, which was a part of the British Isles — but in a different part of time. Haltingly, she sketched a description of a river delta with many branching currents; her point of origin, she explained, was northwest of here.

Llanraw was fondly pictured in her buried remembrances. She described a place where political leaders were chosen by unanimous approval of their families; even one dissenter disqualified them. Children were born only to those genuinely committed to raising them right; forced abortion was the remedy for the uncommitted. Animals were left free to wander as they would, and no human ate meat. Her world had not known war for 283 years. To Paul it was a vision of paradise, and he bought into it. When he learned the truth, it was far too late.3

Ultimately, with his pregnant wife having left him after a row over children, and with his career going smash over indiscretions4 with Arzheen, Paul obtains a dodgy passport for her and flees with her to the south of France. There they live the good vagrant life for a summer, knocking about in places like "the cliff-hung gem of Rocamadour." Then the mistral arrives, bringing with it the undiscovered truth about Arzheen.

She thinks now—or thought this evening—there is only one history after all: No branching river delta, simply a crooked road. They hurled her back along it not for the planned five hundred years, but for something more like ten thousand, to an age when there is still coal, and oil, and unmined ore, being prodigally squandered before our civilization is ruined by its extravagance and collapses so completely that wandering savages out of Central Asia have to learn the art of writing over again from degenerates notching strips of wood with rusty knives. She thought the great empire which fell in the dawn of time and left a few scattered relics for her own people to find might correspond to Rome; discovering that this did not fit, she deduced that it was before Rome's rise that her history branched off. But ultimately she came to the conclusion that the great forgotten civilization must be ours. – Pages 238-9 |

Science fiction is often regarded as the literature of optimism, in which the problems, however formidable they appear, are solved in the end by cleverness and perseverance. There are dystopian tales in the genre, to be sure: enough to be a field of study in themselves. But by and large the description fits. Personal crises are the norm for mainstream novels.

Quicksand might well be classed as a mainstream novel by those who mistakenly disregard the elements Brunner has built into this carefully crafted novel. Arzheen's fighting skills could conceivably come from some oriental martial-arts school. Her unfamiliarity with twentieth-century artifacts could be an act, and her unrecognizable native language could be something fabricated by her undeniably brilliant mind.5 But when they are all part of the same package, the best explanation is the one presented. Even more convincing is the nature of the truth Arzheen finally reveals. In a mainstream novel from 1967, it would be contemporary: something related to the Cold War, perhaps that she was a secret agent sent to infiltrate Britain's military establishment or sabotage some critical installation. Or even that it was all the product of mental illness after all.

And Brunner is to be commended for the skill with which he assembled all the elements of the story. As I say, it is extraordinarily well crafted. And if it is, as a friend might say, "too literary," that does not diminish it for me: literature should be literary. The characters are well drawn, the actions and developments from them are believable. True, the outcome is depressing, as was the outcome of On the Beach. The difference is that Shute's tragedy has the entirety of humanity simply giving up and fading out; in this novel it's only one flawed human being who does so. I therefore award this novel top marks.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.

To contact Chris Winter, send email to this address.